Inhoud

![]() Dossier Papegaaienhumor - Motif J 551.5 - 1.

Moppen - 2. Terug in de tijd

Dossier Papegaaienhumor - Motif J 551.5 - 1.

Moppen - 2. Terug in de tijd

|

|

CuBra |

| 1. Moppen | ||

|

Motif J551.5 Volgens Motif-Index of Folk Literature (Helsinki, 1932-1936) van Stith Thompson Algemene structuur: ... the punishment of a parrot and that bird’s subsequent identification of itself with another animal or a person whose normal appearence is similar to the bird’s mutilated appearence. Neil V. Rosenberg, An annotated collection of parrot jokes (1964)

|

Moppen, uit de archieven van het Papegaaienmuseum

#1. Een man ging met zijn papegaai naar een snoepwinkel. De papegaai vroeg: Mag ik een snoepje? Nee, dat is niet goed voor je, zei de man. Even later weer: Mag ik een snoepje? Ik zei toch al van nee, antwoordde de man. En hup, prompt weer: Mag ik een snoepje? De man boos: Als je het nu nog een keer vraagt, hang ik je aan het plafond. De papegaai keek verschrikt omhoog, en zag een lamp hangen: Heb jij ook om snoepjes gezeurd? (dec. 2006)

#2. Een kapitein heeft een papegaai en die zit altijd op zijn schouder. De kapitein gaat een café binnen en zegt: één whiskey. En een cola roept de papegaai er achter aan. Hé zegt de kapitein, hou je bek jij! Dag daarop komen ze weer in een café, en hetzelfde gebeurt. De dag daarop wéér. Kapitein goed boos: Als je nu nog één keer cola bestelt spijker ik je tegen de muur..! En wanneer de kapitein cola bestelt, bestelt de papegaai zijn cola! Genoeg is genoeg zegt de kapitein, en hij spijkert de papegaai tegen de muur, naast een kruisbeeld. De papegaai kijkt opzij, en vraagt dan: Heb jij ook cola’s besteld..? (1990)

G. Legman, Rationale of the dirty joke (1980) #3. A parrot has the habit of jumping on the hens, and the farmer tells him that if he does that again he will pull out every feather of his head. The parrot jumps on the hens again, and his head-feathers are pulled out. Meanwhil, the farmers’ wife, who has pretentions to culture, is having a formal dinner. She appoints the parrot to the butler and to tell the guests where to put their hats and coats. " Ladies to the right" the parrot announces. "Gentlemen to the left". Suddenly two bald-headed men enter, and the parrot says: " You two chicken-fuckers come out in the henhouse with me." (Motif J2211.2)

En: #4. A parrot sees the minister walk naked through the house to take a bath, and cries: "I see your ass!" He is doused with water in punishment for swearing. Later, when the pastor’s daughter comes in from the rain ans shakes off her wet raincoat, the parrot says: "Whose ass did you see?"

John A. Burrison: Storytellers: folktales & legends from the South, (1991) Bron echter is: G. Legman, No laughing matter: an analysis on sexual humor, 2 (1968)

#5. The parrot goes to church It’s the same parrot. This is a develish parrot, you know. So anyway, this same old parrot and this lady what had the maid hired, her husband was shavin’, and the parrot was lookin’ in the mirror at him while he was shavin’. The parrot said to him: " Look out there, God damn you! You goin’ to cut yourself!" This man says, "All right; if you don’t shut up I’m goin’ to wring you’re neck." Says, "Look out there; God damn it, you’re goin’ to cut yourself!" He says, "I told you, if you don’t hush your mouth I’m goin’ to pull all the feathers out the top of your head." The old man would carry the parrot to church with him every Sunday, y’know. And set him way over in the amen corner or either set him in the pulpit. And so he lived-off again. "Look out there, you goin’ to cut yourself." "I told you, damn it, I was goin’ to pull all the feathers out of your head." So he grabbed him, pulled all the feathers out of his head, and th’owed him back in his cage. So that made the parrot bald-headed. And told him, "Git back in there, you hen-fuckin’ son-of-a-bitch, you!" That’s what he told the parrot. He was mad wit’him, y’know. So he took him to church that day – the same parrot – took him to the church. Old parrot sttin’... he put him way off over there in the corner by hisself, ‘cause he was ashamed of him, see. And they went to havin’service, prayer meetin’, and devotional and everything. And so, the preacher got up preachin’. And things got kindly quiet. Here come in two old bald-headed men, way late. Old parrot looked up and seen’em. Men lookin’ all way round for a seat. Church was full; they couldn’t find a saet. Even the ushers couldn’t find ‘em no seat. Lookin’ all way ‘round. So that parrot flopped his wings, say, : Hey, you two!" Say, "You two hen’fuckin’ son-of-a-bitches, come on over here where I’m at!!"

Internet #6 A farmer and his wife are given the gift of a parrot from a relative. The parrot being a male sneaks out and screws the next door neighbors turkeys and rushes back home before being caught in the act. The next door neighbors knock on the door and explain what the parrot has been doing. The owners of the parrot reprimand him and tell him if he doesn't stop it he's going to shave the parrot's head. That night the parrot, overcome with desire, sneaks out again and screws his neighbors turkeys again. The next morning the owner ties the bird down and proceeds to shave his head. The following morning is the farmers daughter's wedding, and in order to please the relative that gave them the parrot they sit the parrot on a piano and tell him for his punishment he has to greet all the guests and tell them where to sit in the church. The parrot is doing fine. "Groom's side to the left and Bride's side to the right." Then two bald guys walk in and he says, "And you two turkey fuckers, up on the piano with me."

#7 My friend had 2 parrots at home. Not knowing which is male and which female, he became curious and watchfull. He got back from work the next day and found one on the other so he decided to scrape the hair on the head of the one on top to use in identifying which is male. On another fateful day, he had a visitor with a bald head and the male parrot, on sighting the man, started chanting: "Was he caught *****ing also, was he caught *****ing also"

Uit de collectie van het Meertensinstituut, AT 0237 # 8 In een herberg doet een pratende papegaai de stem van de vrouw des huizes na en bestelt twintig mud brandstof. Als de vrouw hierachter komt, geeft ze de vogel zo'n enorme klap dat het hoofd van het dier scheef op de romp komt te staan. Als er even later een man met een zelfde hoofdafwijking de herberg betreedt, vraagt de vogel of hij soms ook twintig mud brandstof heeft besteld.

De papegaai van de kastelein roept de brandstofverkoper 'geef nóg maar tien mud anthrasiet' na nadat de kastelein zelf dezelfde bestelling al heeft gedaan. Als de kastelein in de gaten krijgt dat de papegaai hem een poets gebakken heeft, smijt hij het dier zo hardhandig naar buiten dat de kop de vogel schuin op de romp staat. Als de papegaai meegenomen wordt naar het huis van een pater, vraagt het dier zich vertwijfeld af of Jezus - aan het kruis met de hals schuin - ook om brandstof heeft gevraagd.

Een jongen krijgt van zijn vader op zijn donder omdat hij voor een kwartje tien sinaasappels heeft verkocht in plaats van acht. Als de jongen na de slaag het huis ontvlucht, ziet hij bij een bidhuisje Jezus aan het kruis hangen. Omdat ook Jezus het hoofd schuin heeft en tranen in de ogen, concludeert de jongen 'Jij hebt er zeker ook tien verkocht voor een kwartje'.

Een papegaai bootst de stem van zijn baas na en geeft een koopman opdracht een hele wagenvracht hout af te leveren. Als de baas verneemt dat de papegaai al het hout besteld heeft, geeft hij het dier zo'n vreselijke oplawaai dat het kreupel wordt. Als er een paar dagen later een kreupele man aan de deur komt, zegt de papegaai prompt: 'Ook hout gekocht?'.

Een papegaai bootst de stem van zijn baas na en geeft een koopman opdracht duizend stukken turf te leveren. Als de baas dit merkt, wordt hij zo woedend op de papegaai dat hij het dier met kooi en al op de mesthoop gooit. Als kort daarop een dronken man struikelt en naast de papegaai terecht komt, zegt die prompt 'Jij hebt zeker ook turf besteld'.

Omdat een papegaai het drinkgedrag van een man aan diens vrouw dreigt de verklappen, besluit de man het dier de kop af te snijden. De man geeft de papegaai een haal met een mes en verbergt de vogel zolang in de wc-pot. Als de vrouw kort daarop naar de wc gaat, hoort ze een zielig stemmetje 'Ook stout geweest? Ook een sneetje?' zeggen.

Een ondeugende papegaai verklikt iets. In zijn woede snijdt de heer des huizes bijna de kop van de vogel eraf en gooit de vogel in de wc. De vogel leeft echter nog. Als de vrouw naar de wc moet, zegt de papegaai meewarig 'Hebben ze jou ook de kop afgesneden?'.

Een dominee ruilt zijn vloekende papegaai voor de papegaai van de slager. Als de slager zich op een keer in de vinger snijdt, begint de vogel vreselijk te vloeken. De slager wordt zo boos dat hij het dier een klap geeft. Als de papegaai begint te bloeden, smijt de slager hem in de wc. Als het dienstmeisje op de wc gaat zitten, zegt de papegaai 'heeft de slager jou ook met zijn mes te pakken gehad?'.

De papegaai van een boer vergrijpt zich steeds aan de kippen. Voor straf wordt zijn kop kaalgeplukt en wordt hij in de kelder opgesloten. Op de bruiloft van de boerendochter moet de papegaai voor ceremoniemeester spelen en moet hij zeggen: "Dames links en heren rechts." Als er twee kale mannen binnenkomen, stuurt hij ze naar de kelder.

|

|

| 2. Motief J 551.5 - Terug in de tijd | ||

|

1898 Uitgave van The spiritual couplets of Maulana Jalalu-‘d Din Muhammad Rumi: The Masnavi in de vertaling, uit het Perzisch, van E.H. Whinfield |

Book I, Story 2: The Oilman and his Parrot. An oilman possessed a parrot which used to amuse him with its agreeable prattle, and to watch his shop when he went out. One day, when the parrot was alone in the shop, a cat upset one of the oil-jars. When the oilman returned home he thought that the parrot had done this mischief, and in his anger he smote the parrot such a blow on the head as made all its feathers drop off, and so stunned it that it lost the power of speech for several days. But one day the parrot saw a bald-headed man passing the shop, and recovering its speech, it cried out, "Pray, whose oil-jar did you upset?" The passers-by smiled at the parrot's mistake in confounding baldness caused by age with the loss of its own feathers due to a blow. Confusion of saints with hypocrites Worldly senses are the ladder of earth, Spiritual senses are the ladder of heaven. The health of the former is sought of the leech, The health of the latter from "The Friend." The health of the former arises from tending the body, That of the latter from mortifying the flesh. The kingly soul lays waste the body, And after its destruction he builds it anew. Happy the soul who for love of God Has lavished family, wealth, and goods! Has destroyed its house to find the hidden treasure, And with that treasure has rebuilt it in fairer sort; Has dammed up the stream and cleansed the channel, And then turned a fresh stream into. the channel; Has cut its flesh to extract a spear-head, Causing a fresh skin to grow again over the wound; Has razed the fort to oust, the infidel in possession, And then rebuilt it with a hundred towers and bulwarks. Who can describe the unique work of Grace? I have been forced to illustrate it by these similes. Sometimes it presents one appearance, sometimes another. Yea, the affair of religion is only bewilderment. Not, such as occurs when one turns one's back on God, But such as when one is drowned and absorbed in Him. The latter has his face ever turned to God, The former's face shows his undisciplined self-will. Watch the face of each one, regard it well, It may be by serving thou wilt recognize Truth's face. As there are many demons with men's faces, It is wrong to join hand with every one. When the fowler sounds his decoy whistle, That the birds may be beguiled by that snare, The birds hear that call simulating a bird's call, And, descending from the air, find net and knife. So vile hypocrites steal the language of Darveshes, In order to beguile the simple with their trickery. The works of the righteous are light and heat, The works of the evil treachery and shamelessness. They make stuffed lions to scare the simple, They give the title of Muhammad to false Musailima. But Musailma retained the name of "Liar," And Muhammad that of "Sublimest of beings." That wine of God (the righteous) yields a perfume of musk; Other wine (the evil) is reserved for penalties and pains. |

|

|

1890, London W. A. Clouston: Flowers from a Persian Garden and Other Papers

|

This tale [=The Oilman and his Parrot] is found in the early Italian novelists, (Wie? Waar?) slightly varied, and it was doubtless introduced by Venetian merchants from the Levant: A parrot belonging to Count Fiesco was discovered one day stealing some roast meat from the kitchen. The enraged cook, overtaking him, threw a kettle of boiling water at him, which completely scalded all the feathers from his head, and left the poor bird with a bare poll. Some time afterwards, as Count Fiesco was engaged in conversation with an abbot, the parrot, observing the shaven crown of his reverence, hopped up to him and said: "What! Do you like roast meat too?" | |

|

1890 citaat uit: W. A. Clousto: Flowers from a Persian Garden and Other Papers

|

Here is yet another variant of this droll tale [The grocer and his parrot, zie 1884], which has been popular for generations throughout England, and was quite recently reproduced in an American journal as a genuine "nigger" story: In olden times there was a roguish baker who made many of his loaves less than the regulation weight, and one day, on observing the government inspector coming along the street, he concealed the light loaves in a closet. The inspector having found the bread on the counter of the proper weight, was about to leave, when a parrot, which the baker kept in his shop, cried out: "Light bread in the closet!" This caused a search to be made, and the baker was heavily fined. Full of fury, the baker seized the parrot, wrung its neck, and threw it in his back yard, near the carcase of a pig that had died of the measles. The parrot, coming to itself again, observed the dead porker and inquired in a tone of sympathy: "O poor piggy, didst thou, too, tell about light bread in the closet?" | |

|

1888 Knowles, James Hinton: Folk-tales of Kashmir |

Volgt later in het HPM | |

|

1884 Alfred Cooper Fryer: English Fairy Tales from the North Country |

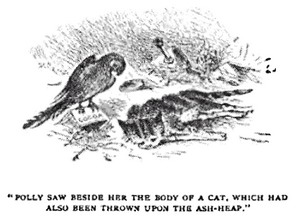

The Grocer and his Parrot There was once a grocer in a small country village — I am not going to tell you where — who possessed a lovely parrot. With its long scaly claws, curved beak, and bright beady eyes, which beamed and twinkled with an expression of sly humour, it very much resembled any other parrot. But the distinguishing beauty of this particular Poil, which rendered it so costly in price and invested it with such a charm in its owner's eyes, was its magnificent grass-green plumage, as long and soft and glossy as silk or spun glass. Like other birds of its kind, this parrot had been trained to speak, and much it loved to exercise its tongue. But as it also had a habit of speaking the truth, it sometimes happened, as we shall presently see that poor Polly got into serious trouble. The grocer had provided for his pet a neat wire cage, which, in fine weather, was hung above the shop door. There, through the long summer afternoons, Polly would sit for hours motionless on her perch, enjoying the warm sunshine, and noting, with keen restless glances, everything that passed in the busy little world around. Out in the street, or in the shop, nothing escaped Polly's observation. One day, when business was slack, and few customers disturbed the quiet of the grocer's shop, Polly watched her master, who paid little heed to the sharp eyes that were looking on, busy himself in mixing sand with his stock of brown sugar. Just as he had finished the dishonest task, an old woman entered and asked for some of that very article. The grocer was preparing, scoop in hand, to weigh out the exact quantity, when suddenly the honest bird cried out, as loud as she could speak, "Sand in the sugar! Sand in the sugar!" Both the grocer and his customer were astounded; but the old woman was the first to recover from her astonishment, and, picking up her money, she walked out of the shop. Then the grocer flew into a rage, as people generally do when they are found out in a mean or wicked action; and taking down the cage, he shook it furiously, till quite a cloud of feathers floated about the shop, like leaves in an autumn gale. Poor Polly, with plumage ruffled, and half dead with terror, cowered in a corner of the cage, while her master shouted, "You abominable bird! If you ever again tell tales of me I will wring your neck; so take warning once for all!" A few days afterwards, in the early morning, just before the shop was opened, Polly saw her master scrape some brick-dust and mix it up with powdered cocoa which he took out of the packets in which it had been sent to him. Then he tied up the packets again and took down the shutters. It was not long before a customer entered - a young workman, with a basket on his arm. He was purchasing articles for his breakfast, and wished to buy a packet of cocoa. But what was his surprise, and the grocer's vexation, when Polly, forgetful of everything but her desire to tell the truth, exclaimed shrilly, " Brick-dust in the cocoa! Brick-dust in the cocoa!" The workman, seeing the guilty expression of the grocer’s face, smiled shrewdly as if he quite understood the parrot's hint, and left the shop without making his purchase. The cruel grocer was ten times more angry than before, and shook the cage till his arm was tired, exclaiming, - You wicked, ungrateful bird! Would you drive away all my customers? Have you forgotten what I told you? The next time you serve me such a trick I shall kill you without mercy!" Poor Polly was thoroughly frightened, and resolved never to speak out again, whatever she might see. But, like some featherless parrots, she found it harder to keep silence than she expected, Time passed, and one day, after her master had been busily engaged for some hours in manufacturing " shop" butter, which was nothing else than lard artfully coloured with a little turmeric, a gaily-dressed lady entered and asked for a pound of fresh butter. "This is really beautiful butter, ma'am," said the deceitful grocer; "it is the best quality, and fresh this morning from the dairy." On hearing this wicked untruth the parrot could control herself no longer, and cried out. loudly, "Lard in the butter! Lard in the butter!" "Scoundrel of a parrot!" shouted the enraged grocer, and rushing to the cage he drew forth the trembling bird, and hastily wringing its neck, flung the body on an ash-heap in the yard at the back of the shop. Polly, however, was not dead; though that was not the fault of her master's intention, for he quite meant to kill her. In a few minutes she began to revive, and venturing to lift up her head, saw beside her the body of a cat, which had also been thrown upon the ash-heap. "Hallo!" she whispered. in rather hoarse tones. "What is the matter with you?" But the cat made no reply; for in truth it had not heard the question, its heart having long ceased to beat. "He is dead!" sighed Polly; "poor fellow! perhaps he, too was afflicted with a love of truth." Then she got upon her feet and tried her wings, "They are sound, at all events," said she, with delight; "I will be off while I can. I will leave this dingy England, and seek some country where truth is venerated." With these words Polly spread her wings and flew swiftly away towards the sun, till she became a mere speck in the distance. Did she ever reach a land where truth is universally venerated? We know not, and we fear not, for it is said that she flew twice round the world and did not find the object of her quest. Perhaps she is flying on still. |

|

|

1879 Memoir of the Rev. Richard Harris Barham

|

The Ingoldsby Legends 'A certain notable housewife (...) had observed that her stock of pickled cockles were running remarkably low, and she spoke to the cook in consequence, who alone had access to them. The cook had noticed the same serious deficiency, - "she couldn't tell how, but they certainly disappeared much too fast!" A degree of coolness, approaching to estrangement, ensued between these worthy individuals, which the rapid consumption of the pickled cockles by no means contributed to remove. The lady became more distant than ever, spoke pointedly and before company, of "some people's unaccountable partiality to pickled cockles," &c. The cook's character was at stake; unwilling to give warning, with such an imputation upon her self-denial, not to say honesty, she, nevertheless, felt that all confidence between her mistress and herself was at an end. 'One day the jar containing the evanescent condiment being placed as usual on the dresser, while she was busily engaged in basting a joint before the fire, she happened to turn suddenly round, and beheld, to her great indignation, a favourite magpie, remarkable for his conversational powers and general intelligence, perched by its side, and dipping his beak down the open neck with every symptom of gratification. The mystery was explained - the thief detected! Grasping the ladle of scalding grease which she held in her hand, the exasperated lady dashed the whole contents over the hapless pet, accompanied by the exclamation - '"Oh, d--me, you've been at the pickled cockles, have ye?" 'Poor Mag, of course, was dreadfully burnt; most of his feathers came off, leaving his little round pate, which had caught the principal part of the volley, entirely bare. The poor bird moped about, lost all his spirit, and never spoke for a year. 'At length when he had pretty well recovered, and was beginning to chatter again, a gentleman called at the house, who, on taking off his hat, discovered a very bald head! The magpie, who happened to be in the room, appeared evidently struck by the circumstance; his reminiscences were at once powerfully excited by the naked appearance of the gentleman's skull. Hopping upon the back of his chair, and looking him hastily over, he suddenly exclaimed, in the ear of the astounded visitor - '"Oh, d--me, you've been at the pickled cockles, have ye?"' |

|

|

1868, London The knight of the Tower Vertaling Thomas Wright |

I wolle telle you an ensaumple of a woman that ete the good morselle in the absence of her husbonde. Ther was a woman that had a pie in a cage, that spake and wolde telle talys that she saw do. And so it happed that her husbonde made kepe a gret ele in a litelle ponde in his gardin, to that entent to yeue it sum of his frendes that wolde come to see hym; but the wyff, whanne her husbond was oute, saide to her maide, '' late us ete the gret ele, and y wille saie to my husbond that the otour hathe eten hym," and so it was done. And whan the good man was come, the pye began to telle hym how her maistresse had eten the ele. And he yode to the ponde, and fonde not the ele. And he asked his wiff wher the ele was become. And she wende to haue excused her, but he saide her, "excuse you not, for y wote welle ye haue eten yt, for the pye hathe told me." And so ther was gret noyse betwene the man and hys wiff for etinge of the ele. But whanne the good man was gone, the maistresse and the maide come to the pie, and plucked of alle the fedres on the pyes hede, saieng, "thou hast discouered us of the ele;" and thus was the pore pye plucked. But euer after, whanne the pie sawe a balled or a pilled man, or a woman with an highe forhede, the pie saide to hem, "ye spake of the ele." And therfor here is an ensaumple that no woman shulde ete no lycorous morcelles in the absens and withoute weting of her husbond, but yef it so were that it be with folk of worshippe, to make hem chere; for this woman was afterward mocked for the pye and the ele. |

|

| Hiermee zijn we gekomen bij wat de Europese oerbron lijkt van motief J 551.5, het volksboek dat bekend staat onder vele titels, waaronder Le livre du chevalier de la tour Landry, The Knight of the Tower, en Der Ritter vom Turm. De oorsprong van de vertelling ligt in India. |

|

|

|

1868, Dublin The knight of the Tower

1854, Paris Le livre du chevalier de la tour Landry

1572, Franckfurt am Mayn Der Ritter vom Turm

1519, Strassburg Der Ritter vom Turn

1514, Paris Le chevalier de la tour

1513, Basel Der Ritter vom Turn

1495, Augsburg Der Ritter vom Turn

1493, Basel Der Ritter vom Turn

1484, London The knight of the Tower

1371-1373 Geoffroy de La Tour-Landry schrijft wat is komen te heten: Le chevalier de Tour-Landry Livre pour l’enseignement de ses filles

1258-1273 Maulana Jalalu-‘d Din Muhammad Rumi schrijft: The Masnavi, waarin opgenomen: De oliehandelaar en de papegaai (voor Engelse vertaling zie 1898)

Het verhaal komt naar alle waarschijnlijkheid uit het Sanskriet, India. Bron opsporen.

Shuka-Saptati (Zeventig verhalen van een papegaai)latere versie: papegaai houdt vrouw aan de praat, maanden lang, tijdens afwezigheid van haar man. |

||

|

|

||